Eddie Barnes

Eddie is Director of Our Scottish Future

After the row over Nicola Sturgeon’s Covid conduct subsides, the deep flaws exposed by the pandemic will still afflict the UK. Time for a British repair job.

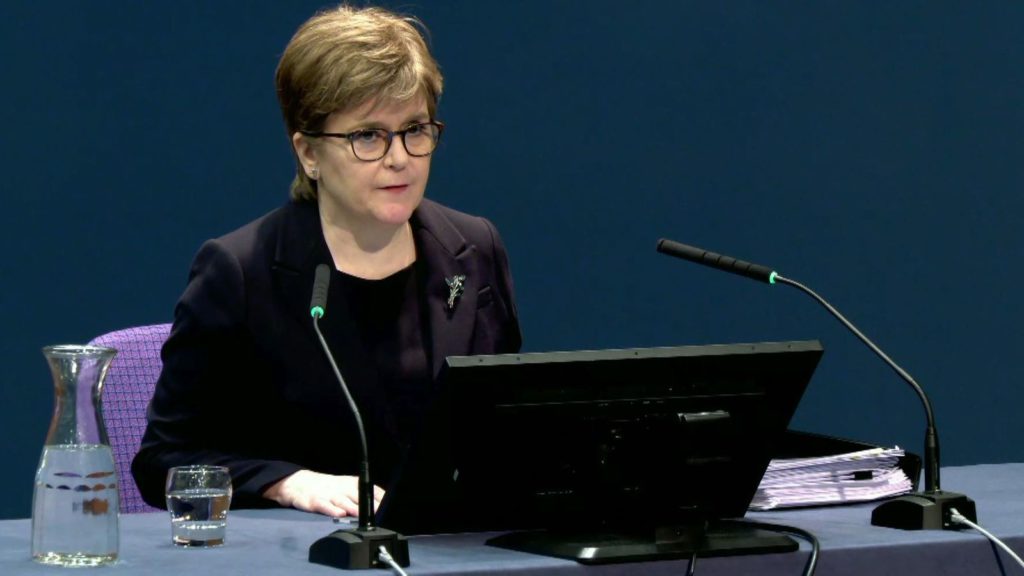

Nicola Sturgeon’s decision to delete her WhatsApp messages during the Covid crisis, despite having promised not to, has been the central story of the Inquiry this week.

There are plenty of pertinent questions around that which remain hanging. But while the personal fate of Nicola Sturgeon has occupied most of our attention, it should not blind us to some of the wider themes and lessons that emerged from her evidence.

Take one: the functioning of the UK state and the relationship between Scotland and Whitehall. Surely if nothing else, the inquiry has shown all of us that it is in need of serious reform.

To help consider this dispassionately, let’s imagine for a moment that instead of Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland was being run by somebody else entirely back in early 2020. Somebody like Manchester mayor Andy Burnham for example. Or Ruth Davidson. Or Anas Sarwar.

And then let us imagine too that instead of Boris Johnson sitting at the other end of the phone, there was somebody else as well. Somebody a little more switched on: a Rishi Sunak for example, or a Theresa May, or a David Cameron. Would it all have been sweetness and light between Scotland and London in those circumstances? Or would there still have been problems in the way Scotland and Westminster worked together?

Certainly matters might have been a little less confrontational. Whitehall wouldn’t have been quite so chaotic. Number Ten would have been a little more communicative. And though a First Minister Burnham, Davidson or Sarwar might still have disagreed with individual decisions taken by London, they might have been less quick to emphasise their differences than was Sturgeon.

UK Ministers would probably have been less prickly in response. Trust between the governments would, broadly, have held. The very fact that both ends of the phone in London and Edinburgh were in favour of the UK sticking together would have helped smooth matters over considerably.

So – yes – it would have been better. But whether it was Burnham, Davidson or Sarwar who happened to be in the hot seat in the spring of 2020, I wager that any or all of them would have rubbed up against some of the problems that occur when Scotland deals at close hand with the UK state. These issues go beyond the personalities of the moment. And it’s these matters which, once the dust settles on this last week, Scottish pro-union politicians should pay keen attention to.

But whether it was Burnham, Davidson or Sarwar who happened to be in the hot seat in the spring of 2020, I wager that any or all of them would have rubbed up against some of the problems that occur when Scotland deals at close hand with the UK state

Eddie Barnes Tweet

In a statement published by the Inquiry this week, they were summarised by Ms Sturgeon herself. When the pandemic hit first, she said, the governments rubbed along fine. They laid down their constitutional differences at the door. As she wrote in her statement, the cordial move quickly evaporated, however:

“Tensions arose when it became obvious that a Four Nations approach did not simply mean that UK government decisions, even in areas of devolved responsibility, would be applied automatically and by default in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Instead of understanding and respecting the distinct responsibilities and lines of accountability of the DAs — and the duties these placed on us — there seemed to be an assumption on the part of the UK government that when we had different opinions or reached decisions different to those they were taking, we were being ‘political’. I think this assumption was particularly strong in relation to the Scottish Government. Whatever the political disagreements that coloured the UK government’s opinion of the Scottish Government, I strongly feel that in the context of the pandemic this assumption was deeply unfair, unjustified, and unsubstantiated. It also highlights a more general issue — that while UK government ministers may understand the theory of devolution, they struggle with its practical application.”

To my mind, Mrs Sturgeon protests too much here. UK Ministers were justified in reaching the conclusion that politics played a role in Ms Sturgeon’s decision-making. To my mind, that she doesn’t see it that way is a function of her nationalism.

But – let it be said – there’s still something to what she says. On the more general issue, as she puts it, she makes an obvious point. UK Ministers undoubtedly have a problem with the practical application of devolution. It was undoubtedly exposed by the Covid crisis. There’s still a view that Whitehall say-so should be automatically obeyed.

People may find it difficult to agree with Mrs Sturgeon. It’s worth therefore, comparing her points with those held by Andy Burnham. Famously Mr Burnham found out about restrictions on movement in Manchester when they appeared on a news feed on his phone in the middle of a press conference.

In his own statement handed to the Inquiry last year, he concluded that the experience:

“…revealed to me that the approach to the pandemic was overly top down and overly centralised….This was most clearly illustrated in the arrangements for contact tracing which led to an ineffective, outsourced national system being established which failed to support local areas. At all times, the national response was characterised by a lack of adequate consultation and poor communications. It frequently felt chaotic. Repeated requests were made that regional Mayors be invited to join COBR but, despite this, only the Mayor of London attended regularly and the Mayor of the Liverpool City Region on one occasion. This, I believe, led to a London-centricity in decision making and failed to consider equally the needs of all regions when national policy was being decided.

So strip aside the politics and forget Mrs Sturgeon for a minute. What Covid demonstrated is that Britain has a governance problem. We can have, if we want, a highly centralised way of working where London sends out orders for the entire country to follow. We can have, if we want, a more decentralised command structure where the various layers of government in the nations and regions of the UK are in charge. But we will struggle, surely, when we have a system which tries to do both at the same time.

So what to do? Create better structures? In her evidence, Ms Sturgeon runs through the myriad groups on which UK Ministers and devolved administrations sat on during the crisis. Their effectiveness, she claims, was “not due to the strength or otherwise of the structural arrangements, but to the culture and mindset that the different governments brought to bear and the levels of trust and mutual respect that existed between us”.

What Covid demonstrated is that Britain has a governance problem

Eddie Barnes Tweet

Rather than structures, her evidence illustrates the importance of personal relationships. Michael Gove “tried hardest to understand the positions of the DAs”, she notes. But then he struggled to deliver, she claims. Had David Cameron or Theresa May been in office, they “would have had more regular and direct contact with the DAs”, she notes. Instead Boris Johnson decided to palm her off.

Yet, at the same time, and even when there’s a man like Mr Johnson in charge, better structures could surely have helped. Mrs Sturgeon herself notes that she was “frustrated…by my inability to engage directly with SAGE” (the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies). As with Mr Burnham, she also expressed annoyance that the UK emergency panel COBR didn’t not have an “understanding of the responsibilities and lines of accountability of the DAs”. There’s an obvious solution here: make them more accountable to politicians outside the M25.

Our Scottish Future set out some further ideas 18 months ago when we first looked at this issue. The report is here. Doubtless, in time, Lady Hallett’s Inquiry will end up offering recommendations too.

Nicola Sturgeon no longer has any political power. When the next pandemic hits, it’s quite possible the SNP won’t be in charge either. In other words, the weaknesses exposed by Covid may well fall on the desk of a Labour-led government in Scotland which will discover, in time, that they are now their problems to tackle.

Hoping that you can form a decent personal relationship with key Ministers in London isn’t a satisfactory basis on which to run a complex country in the middle of a crisis. Fixing the structural weaknesses revealed by Covid is a task that a pro-UK Government in Scotland will need to tackle.

The next time, Britain needs to work better.